- Fundraising for the Rest of Us

- Posts

- Is your problem "too niche"?

Is your problem "too niche"?

Here is how to frame your problem space to investors - especially for the rest of us.

Hey friends,

Last week, we talked about YOUR story and whether investors really care. (Spoiler: they do.) I’m a big proponent of leading with your personal story when pitching, because every investment starts with a human-to-human connection.

If you missed that newsletter, you can catch up here:

Once investors understand you and your why, it’s time to paint a picture of the problem you’re solving. But what if they don’t get your problem space? What if they call it “niche?”

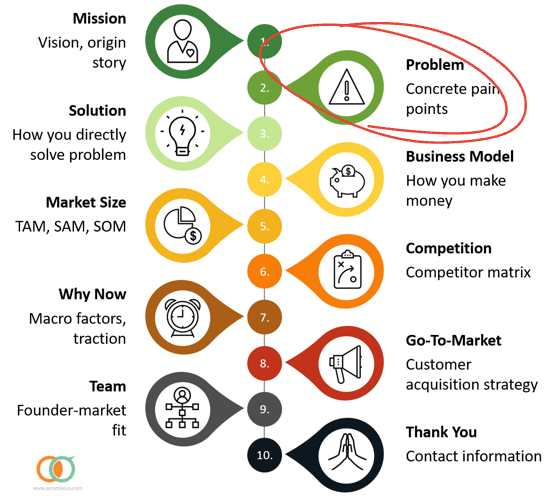

In Chapter 7 of Fundraising for the Rest of Us, I break down the Problem section of the Core 10 Pitch Framework. Below is a brief overview, and a look at how this part of the pitch shows up differently for the rest of us.

Want to read the full chapter and help shape the book? Apply to be a beta reader.

Let’s get into it!

Anchor the Problem to Your Story

A strong problem section often flows naturally from your origin story. Many great startups start with someone experiencing a problem and saying, “There has to be a better way.” Ask yourself:

What is the exact problem we’re solving for? It’s often a piece of a larger issue.

Who, specifically, is feeling this pain?

How big is it – really?

Would someone actually pay to fix it?

The goal of every slide in your pitch deck is to address a certain aspect of risk that investors might see when evaluating your company.

By clearly articulating your problem, you’re removing the risk that:

There’s no real problem.

No one is feeling it strongly enough.

It can’t realistically be solved.

However, articulating this problem is different for those of us who don’t look like the investors we’re pitching, or have backgrounds and markets that investors don’t understand.

How it’s Different for the Rest of Us

Proving a problem exists can feel like an uphill battle, especially when it disproportionately impacts a community investors haven’t personally experienced.

This puts you in a defensive position, not unlike being asked prevention questions instead of promotion ones, where you need to explain both what the problem is and why it matters. This creates an extra burden to overprove what may be intuitively obvious to others with shared experience.

Even worse, if your problem ties to systemic inequities like funding gaps, lack of access, or representation, you might hit subtle (or overt) resistance. Acknowledging the problem often means acknowledging a system investors may benefit from, which adds friction to the conversation.

The more “niche” your problem sounds to a homogenous investor base, the more intentional you need to be in using data and framing it as a high-upside opportunity rather than a special-interest plea. Here are some tips to tilt the odds back in your favor:

Translate lived experience into data

Tell the personal story and quantify it. Personal insight alone can be dismissed as anecdotal, especially if investors don’t share your background. Use external data and secondary sources to validate the problem. Otherwise, you’re asking investors to trust your word on an unfamiliar issue, which is a tough ask if they don’t know or relate to you.

Data builds credibility and reframes your story as a market signal.

Use language that reframes the problem as a profitable opportunity

Underserved markets = undervalued markets.

This shifts from a deficit-based frame to an opportunity-based one. Underserved focuses on who isn’t getting enough, which can lead investors to view these markets as risky, difficult, or burdened by challenges. Undervalued tells a different story of hidden potential that others have missed. It reframes the narrative to match what investors are ultimately seeking, opportunities with financial upside, and shows there are paying customers waiting in the market.

Tie the problem to a demographic trend or economic shift

What may seem like a niche issue becomes a compelling opportunity when it’s positioned within a broader movement.

Investors are more likely to engage when they see that your solution taps into where the market is already headed, not just where it’s been. Anchor your problem in undeniable trends like shifting consumer behavior, rising purchasing power in specific populations, or evolving regulatory and policy environments. This helps reframe your insight as timely and scalable rather than fringe.

For the rest of us, it also reduces the burden of “proving” your market by showing that larger forces are already validating its growth.

That’s it for now. In the book, I break down exactly how to design your Problem slide and the conversation around it. Want to read more now? Apply to be a beta reader and join our founder community!

Allison